- Home

- Jamie Ford

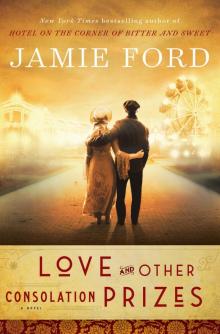

Love and Other Consolation Prizes

Love and Other Consolation Prizes Read online

Love and Other Consolation Prizes is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination, or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2017 by Jamie Ford

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

BALLANTINE and the HOUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Ford, Jamie, author.

Title: Love and other consolation prizes: a novel / Jamie Ford.

Description: New York: Ballantine Books, 2017.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017029513 | ISBN 9780804176750 (hardcover: acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780804176767 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Families—Fiction. | Brothels—Fiction. | Friendship—Fiction. | Domestic fiction. | BISAC: FICTION / Literary.

Classification: LCC PS3606.O737 L69 2017 | DDC 813/.6—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017029513

Ebook ISBN 9780804176767

randomhousebooks.com

Image on title page and on this page courtesy of University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, Nowell x 1275.

Book design by Victoria Wong, adapted for ebook

Cover design: Laura Klynstra

Cover illustration: Ilina Simeonova, including images © Alamy Stock Photo/Historic Collection (exposition buildings, Ferris wheel)

v4.1

ep

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Overture

Raining Stars

Unbound

The Water Trade

Juju Reporting

The Floating World

Everyone Plays, Nobody Wins

Rising from Grace

Native Tongues

Healthy Boy, Free

Tenderloin

Crusaders of Wappyville

Welcome to the Future

Mayflower Rock

Dragon’s Blood

Old Man on Campus

Precious Jewel

Boston Marriage

Stroll on the Pay Streak

Stars, Falling

Ruby Chow’s

Angels in the Snow

B Sides

Cloudy Days

Sunny Days

Coming Out, Going Away

Anger Is Your Currency

Bedside

Cardboard and Lace

Five Thousand Reasons

All I Have to Give

Crossroads

Still

Faded

Unspoken

Whispers of Calliope

Lit the Fire

Vagrants

Prize and Consolations

Love and Marriage

Meet Me at the Fair

Secrets of Show Street

Twice in a Lifetime

Closing Ceremonies

Author’s Note

Dedication

Acknowledgments

By Jamie Ford

About the Author

Pleading moments we knew

I will set them apart

Every word, every sign

Will be burned in my heart.

—from “Non, je ne regrette rien,” performed by Edith Piaf

OVERTURE

(1962)

Ernest Young stood outside the gates on opening day of the new world’s fair, loitering in the shadow of the future. From his lonely vantage point in the VIP parking lot, he could see hundreds of happy people inside, virtually every name in Seattle’s Social Blue Book, wearing their Sunday best on a cool Saturday afternoon. The gaily dressed men and women barely filled half of Memorial Stadium’s raked seating, but they sat together, a waterfall of wool suits and polyester neckties, cut-out dresses and ruffled pillbox hats, cascading down toward a bulwark of patriotic bunting. Ernest saw that the infield had been converted to a speedway for motorboats—an elevated moat, surrounding a dry spot of land where the All-City High School Band had assembled, along with dozens of reporters who milled about smoking cigarettes like lost sailors, marooned on an island of generators and television cameras. As the wind picked up, Ernest could smell gasoline, drying paint, and a hint of sawdust. He could almost hear carpenters tapping finishing nails as the musicians warmed up.

Saying that Ernest wished he could go inside and partake of the celebration was like saying he wished he could dine alone at Canlis restaurant on Valentine’s Day, cross the Atlantic by himself aboard the Queen Mary, or fly first class on an empty Boeing 707. The scenery and the festive occasion were tempting, but the endeavor itself only highlighted the absence of someone with whom to share those moments.

For Ernest, that person was Gracie, his beloved wife of forty-plus years. They’d known each other since childhood, long before they’d bought a house, joined a church, and raised a family. But now their memories had been scattered like bits of broken glass on wet pavement. Reflections of first kisses, anniversaries, the smiles of toddlers, had become images of a Christmas tree left up past Easter, a package of unlit birthday candles, recollections of doctors and cold hospital waiting rooms.

The truth of the matter was that these days Gracie barely remembered him. Her mind had become a one-way mirror. Ernest could see her clearly, but to Gracie he’d been lost behind her troubled, distorted reflection.

Ernest chewed his lip as he leaned against the vacant Cadillac De Ville that he’d spent the better part of the morning polishing. He felt a sigh of vertigo as he stared up at the newly built Space Needle—the showpiece of the Century 21 Expo—the talk of the town, if not the country, and perhaps the entire world. He was supposed to deliver foreign dignitaries to the opening of the Spanish Village Fiesta, but the visitors had been held up—some kind of dispute with the Department of Immigration and Naturalization Services. So he came anyway, to try to remember the happier times.

Ernest smiled as he listened to Danny Kaye take the microphone and read a credo of some kind. The Official World’s Fair Band followed the famous actor as they took over the musical duties for the day and began to play a gliding waltz. Ernest counted the time, one-two-three, one-two-three, as he popped his knuckles and massaged the joints where arthritis reminded him of his age—sixty-four, sixty-five, sixty-something, no one knew for sure. The birth date listed on his chauffeur’s permit had been made up decades earlier, as had the one on his old license with the Gray Top Taxi company. He’d left China as a boy—during a time of war and famine, not record keeping.

Ernest blinked as the waltz ended and a bank of howitzers blasted a twenty-one-gun salute somewhere beyond the main entrance, startling him from his nostalgic debridement. The thundering cannons signaled that President Kennedy had officially opened the world’s fair with the closing of a telegraph circuit sent all the way from his desk at the White House. Ernest had read that the signal would be bounced off a distant sun, Cassiopeia, ten thousand light-years away. He looked up at the blanket of mush that passed for a northwestern sky, and made a wish on an unseen star as people cheered and the orchestra began playing the first brassy strains of “Bow Down to Washington” while balloons were released, rising like champagne bubbles. Some of the nearby drivers honked their horns as the Space Needle’s carillon bells began ringing, heralding the space age, a clarion call that was drowned out by the deafening, crackling roar of a squadron of fighter jets that boomed overhead. Ernest felt the vibration in his bones.

<

br /> When Mayor Clinton and the City Council had broken ground on the fairgrounds three years ago—when a gathering of reporters had watched those men ceremoniously till the nearby soil with gold-plated shovels—that’s also when Gracie began to cry in her sleep. She’d wake and forget where she was. She’d grow fearful and panic.

Dr. Luke had told Ernest and their daughters, with tears in his eyes, “It’s a rare type of viral meningitis.” Dr. Luke always had a certain sense of decorum, and Ernest knew he was lying for the sake of the girls. Especially since he’d treated Gracie when she was young.

“These things sometimes stay hidden and then come back, decades later,” the doctor had said as the two of them stood on Ernest’s front step. “It’s uncommon, but it happens. I’ve seen it before in other patients. It’s not contagious now. It’s just—”

“A ghost of red-light districts past,” Ernest had interrupted. “A ripple from the water trade.” He shook Dr. Luke’s hand and thanked him profusely for the late-night house call and the doctor’s ample discretion regarding Gracie’s past.

Ernest remembered how shortly after his wife’s diagnosis her condition had worsened. How she’d pulled out her hair and torn at her clothing. How Gracie had been hospitalized and nearly institutionalized a month later, when she’d lost her wits so completely that Ernest had had to fight the specialists who recommended she be given electroshock therapy, or worse—a medieval frontal-lobe castration at Western State Hospital, the asylum famous for its “ice pick” lobotomies.

Ernest hung on as Dr. Luke quietly administered larger doses of penicillin until the madness subsided and Gracie returned to a new version of normal. But the damage had been done. Part of his wife—her memory—was a blackboard that had been scrubbed clean. She still fell asleep while listening to old records by Josephine Baker and Edith Piaf. She still smiled at the sound of rain on the roof, and enjoyed the fragrance of fresh roses from the Cherry Land flower shop. But on most days, Ernest’s presence was like fingernails on that blackboard as Gracie recoiled in fits of either hysteria or anger.

I didn’t know the month of the world’s fair groundbreaking would be our last good month together, Ernest thought as he watched scores of wide-eyed fairgoers—couples, families, busloads of students—pouring through the nearby turnstiles, all smiles and awe, tickets in hand. He heard the stadium crowd cheer as a pyramid of water-skiers whipped around the Aquadrome.

To make matters worse, when Gracie had been in the hospital, agents from the Washington State Highway Department had showed up on Ernest’s doorstep. “Hello, Mr. Young,” they’d said. “We have some difficult news to share. May we come in?”

The officials were kind and respectful—apologetic even. As they informed him that his three-bedroom craftsman home overlooking Chinatown, along with his garden and a row of freshly trimmed lilacs in full bloom—the only home he’d ever owned and the place where his daughters took their first steps—all of it was in the twenty-mile urban construction zone of the Everett-Seattle-Tacoma Freeway. The new interstate highway was a ligature of concrete designed to bind Washington with Oregon and California. In less than a week, he and his neighbors had been awarded fair-market value for their properties, along with ninety days to move out, and the right-of-way auctions began.

The government had wanted the land, Ernest remembered, and our homes were a nuisance. So he’d moved his ailing wife in with his older daughter, Juju, and watched from the sidewalk as entire city blocks were sold. Homes were scooped off their foundations and strapped to flatbed trucks to be moved or demolished. But not before vandals and thieves stripped out the oak paneling that Ernest had installed years ago, along with the light fixtures, the crystalline doorknobs, and even the old hot-water heater that leaked in wintertime. The only thing left standing was a blur of cherry trees that lined the avenue. Ernest recalled watching as a crew arrived with a fleet of roaring diesel trucks and a steam shovel. Blossoms swirled on the breeze as he’d turned and walked away.

As a young man, Ernest had carved his initials onto one of those trees along with Gracie’s—and those of another girl too. He hadn’t seen her in forever.

As an aerialist rode a motorcycle on a taut cable stretched from the stadium to the Space Needle, Ernest listened to the whooshing and mechanical thrumming of carnival rides. He caught the aroma of freshly spun cotton candy, still warm, and remembered the sticky-sweet magic of candied apples. He felt a pressing wave of déjà vu.

The present is merely the past reassembled, Ernest mused as he pictured the two girls and how he’d once strolled with them, arm in arm, on the finely manicured grounds of Seattle’s first world’s fair, the great Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, back in 1909. When the city first dressed up and turned its best side to the cameras of the world. He remembered a perfect day, when he fell in love with both girls.

But as Ernest walked to the gate and leaned on the cold metal bars, he also smelled smoke. He heard fussy children crying. And his ears were still ringing with the echoes of the celebratory cannons that had scared the birds away.

He drew a deep breath. Memories are narcotic, he thought. Like the array of pill bottles that sit cluttered on my nightstand. Each dose, carefully administered, use as directed. Too much and they become dangerous. Too much and they’ll stop your heart.

RAINING STARS

(1902)

Yung Kun-ai watched his little mei mei struggle to breathe. His newborn sister was only two days old—a half-breed like him, without a father. She mostly slept, but when she did wake, she coughed until she cried. Then cried until she was desperately gasping for air. Her raspy wailing made her seem all the more out of place, unwelcome; not unloved, just tragically unfit for this world.

Yung understood that feeling as his sister stirred and keened again, scaring away a pair of ring-necked crows from a barren lychee tree. The birds cawed, circling. Yung’s mother should have been observing her zuoyuezi, the traditional time of rest and recovery after childbirth. Instead, she’d staggered into the village cemetery, dug a hole in the earth with her bare hands, and placed his sister’s naked, trembling body inside. As Yung stood nearby, he imagined that the ground must have been warm, comforting, since it hadn’t rained in months, the clay soil surrounding his unnamed sibling like a blanket. Then he watched his mother pour a bucket of cold ash from the previous night’s fire over his sister’s body and she stopped crying. Through a cloud of black soot he saw tiny legs jerk, fragile arms go still. Yung didn’t look away as his lowly parent smothered his baby sister, or while his mother wearily pushed the dirt back into the hole, burying his mei mei by scoops and handfuls. His mother tenderly patted the soil and replaced the sod before pressing her forehead into the grass and dirt, whispering a prayer, begging forgiveness.

Yung swallowed the lump in his throat and became a statue. At five years old, he could do nothing else. The bastard son of a white missionary and a Chinese girl, he was an outcast in both of their worlds. He and his mother were desperately poor, and a drought had only made their bad situation worse. For months they’d been eating soups made from mossy rocks and scraps of boiled shoe leather his mother had scavenged from the dying. When she turned and saw what Yung had witnessed she didn’t seem shocked, or apologetic. She didn’t bother to wipe away the ashen tears that framed the pockmarked hollows of her cheeks, or the dust and grime that had settled into her scalp where her hair had thinned and fallen out. She merely placed a filigreed hairpin in his hand and folded his tiny fingers around the tarnished copper and jade phoenix that represented the last of their worldly possessions. She knelt and hugged him, squeezed him, ran her dirty fingers through his hair. He felt her bony limbs, the sweet smell of her cool skin as she kissed his face.

“Only two kinds of people in China,” she said. “The too rich and the too poor.”

He’d remembered combing the harvested fields for single grains of rice, gathering enough to make a tiny handful that they would share while the well-fed children flew

kites overhead. His empty stomach reminded him of who he was.

“Stay here and wait for your uncle,” she said. “He’s going to take care of you now. He’s going to take you to America. He’s going to show you a new world. This is my gift to you.”

Yung’s mother addressed him in Cantonese and then in the little bit of English they both understood. She told him he had his father’s eyes. And she spoke about a time when they would be together again. But when she tried to smile her lips trembled.

“Mm-goi mow hamm,” Yung said as she turned away. “Don’t cry, Mama.”

Yung wasn’t sure if the man he was supposed to wait for was truly his uncle, but he doubted it. The best he could hope was that the man might be one of the rich merchants who specialized in the poison trade or the pig trade, because dealing with men who smuggled opium or people would be preferable to members of the Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists, the Chinese boxers who had been slaughtering missionaries, foreigners, and their offspring. Equally dangerous were the colonial soldiers sent to put down the rebellion. The villagers, including Yung’s father, had been caught in the siege, the melee, and now the maelstrom. That’s when his mother must have known that the end of their world was near—when they saw the starving fishermen hauling in their nets, filled with the bodies of the dead.

As Yung watched his mother disappear, leaving him alone in the cemetery, he wanted to yell, “Ah-ma! Don’t leave me!” He wanted to run to her, to cling to her legs, to cry at her feet, begging. But he resisted, even as he whimpered, yearning. He did what he was told as he ached with sadness and loneliness. He had always obeyed her—trusted her. But it seemed as if she had died months earlier, and all that remained was a ghost, a skeleton—a hopeless broken spirit with no place left to wander and no one to haunt.

What little hope she had, she’d bequeathed to him.

So he waited, grieving, as the sun set upon the place where his mei mei had been interred. He remembered his Chinese grandmother and how she’d once talked about the Lolos, the tribal people of Southern China who believed that there was a star in the sky for every person on Earth. When that person died, their star would fall.

Songs of Willow Frost

Songs of Willow Frost Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet

Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet Love and Other Consolation Prizes

Love and Other Consolation Prizes Songs of Willow Frost: A Novel

Songs of Willow Frost: A Novel